ICEMAN ELSEWHERE

ICEMAN ELSEWHERE

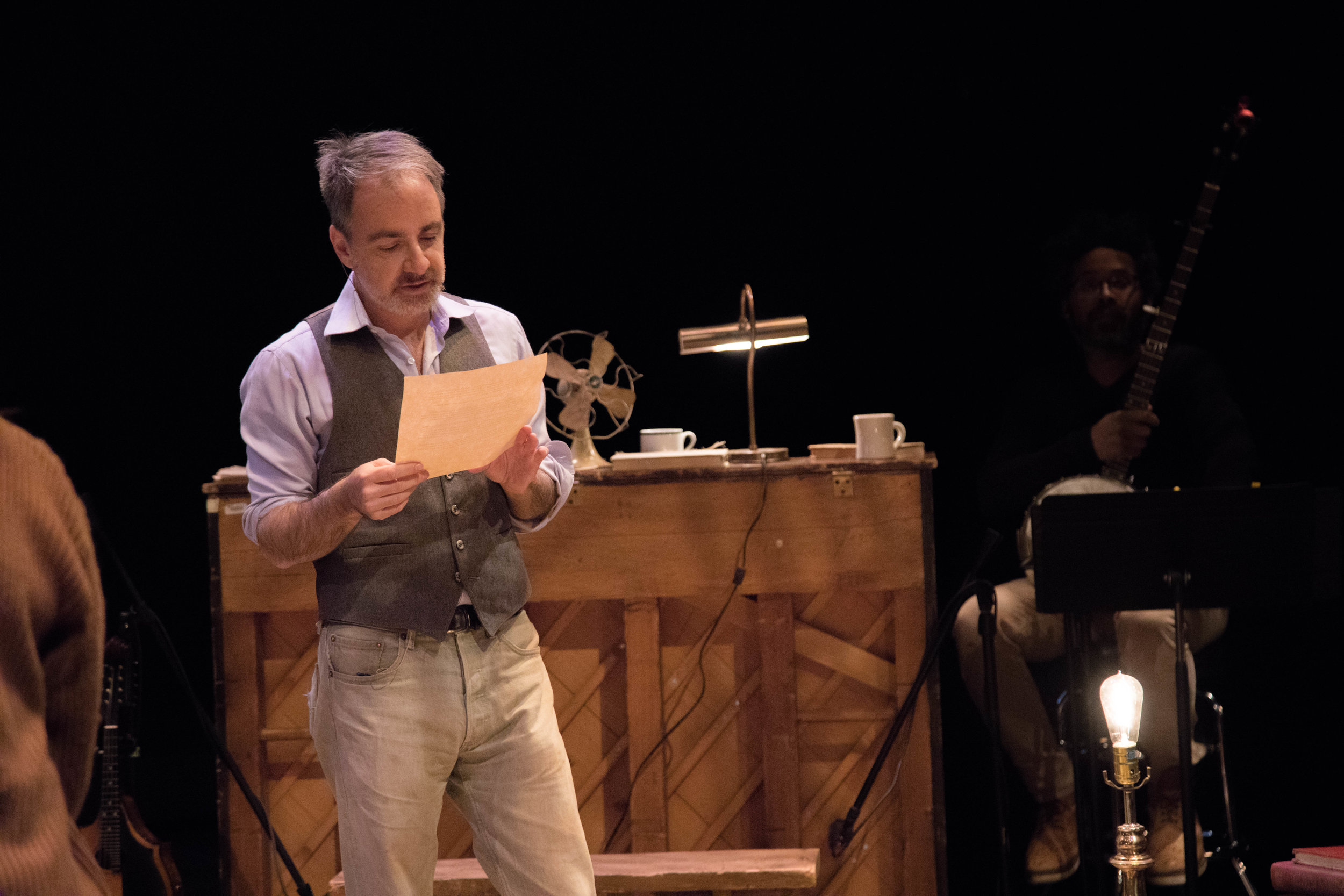

By Howard Fishman

April 26, 2018

I loved “St. Elsewhere” when I was a kid growing up in West Hartford, CT. Every Wednesday night, without fail, I would tune in to Channel 30 at 10pm, and watch the show. “Elsewhere” had a true ensemble cast that worked together to draw subtleties of humor, sensitivity and depth out of their finely-drawn characters and from the smart scripts that stretched plotlines out over entire seasons (rare in those days). Like its stylistic cousin “Hill Street Blues,” “Elsewhere” was a moody, downbeat soap opera; death and heartbreak were ever-present. There was something meta about it too, before that word came into common parlance and practice; as far as ratings went, it was a failing show, always in danger of being cancelled, set in a failing hospital, always in danger of being shut down. A melancholy air infused the show, an underdog sensibility that made one root for both the characters and the series itself. Every time it was renewed for another season my early-adolescent soul rejoiced. When the show finally did reach its end, after six seasons, I was broken up about it. It had only been five years since the finale of “M*A*S*H” and here I was saying goodbye to what felt to me like another surrogate family (interestingly enough, another bunch of doctors).

The cast was a mix of veterans (led by Ed Flanders, Norman Lloyd, Christina Pickles, David Birney, and William Daniels) and young then-unknowns (Ed Begley, Jr., Mark Harmon, Howie Mandel, David Morse, and Denzel Washington). Their characters seemed to really communicate with one another, to truly inhabit the make-believe world they’d been cast in. I was unexpectedly reminded of this when the curtain came down on the current revival of “The Iceman Cometh” (now at the Jacobs Theater on Broadway) and I looked at my program for the first time to learn that the actor who had so uncomfortably and unconvincingly portrayed Denzel Washington’s foil in the show had been none other than his erstwhile “Elsewhere” cast member, David Morse.

How could this be? These two fine actors had established a rapport over six long seasons of that show, more than three decades ago. They shared a rich, nuanced history. “Elsewhere” may have finally lost its terminal battle against a popular mandate for more light-hearted entertainment, but it had been a noble fight, fought with gusto and lost with dignity. These guys had spent years giving something they cared about all that they had. Of course, Washington’s career had burst forth after “Elsewhere” in glittering Hollywood style, while Morse’s has been less visible, mostly spent playing character roles like his sad-eyed, quiet George Washington in “John Adams,” but this bit of casting for “Iceman” would seem to have been, on paper, an inspired choice: the former cast-mates reunited once again in another ensemble piece with no less than life and death as its subject, this time pitted against one another as Larry Slade and Theodore (“Hickey”) Hickman, two old friends meeting up again for the last time.

Before delving into the particulars of Morse’s performance, it should be noted that playing Larry Slade is no easy assignment for any performer. Even seasoned O’Neill actor Brian Dennehy seemed to struggle with the role in Robert Falls’ majestic revival at BAM, three seasons ago. While it’s a fact that whomever is cast as Hickey has always received top billing (owing, perhaps, to Jason Robards’s early, career-making turn in Jose Quintero’s landmark 1956 mounting at Circle in The Square -- a production that effectively gave the Off-Broadway movement its first teeth), the case can and has been made that Larry Slade is the more demanding of the two roles, and that it is he, and not Hickey, who is really the protagonist of the piece. Larry is simultaneously the audience’s guide and the playwright’s mouthpiece. He is the one who espouses O’Neill’s most philosophical views, asks his most existential questions, states (and restates) his main themes. Larry is concertmaster here, first chair violin. He has, by far, the most dialogue of any of the eighteen main characters. Aside from Rocky (the bartender whose job it is to oversee the establishment in which the play takes place), and the somnolent Hugo (a drunk who spends much of the play in a barely-conscious stupor), Larry is the only character who remains present for the play’s action throughout. He is the only character who is witness to the entirety of the proceedings, which -- even in this trimmed version -- still clocks in just shy of four hours.

Hickey, the “star” of the show, does not even enter until nearly an hour into the performance, at the very end of the first act. He arrives on a mission to relieve his old friends of their illusions, their “pipe dreams” about tomorrow that they individually cling to (i.e. tomorrow I’ll quit drinking; tomorrow I’ll go looking for a new job; tomorrow I’ll reclaim my former glory). Because of a self-imposed time constraint, Hickey moves quickly and appears sporadically, coming and going, until he finally delivers his epic, confessional monologue in Act Four. But it is Larry who watches the whole unfold; it is through Larry’s eyes that reality begins to twist and fragment in Acts Three and Four as O’Neill’s theatrical language somehow manages to seamlessly transition from easy naturalism to outright expressionism; it is Larry whose character undergoes the only real transformation when the play is through. As he says in his final speech “I’m the only real convert... Hickey made here!” As the final, awful moments of “Iceman” play out, the teeming ensemble of bums and drunks snap back into place, reclaiming the exact, pathetic identities they’d inhabited at the top of the play. Despite the moral reckoning prompted by Hickey’s visit, by the end it is as if nothing whatever had happened to them (making one of Hickey’s final lines “It was a waste of time, my coming here” really hurt; it’s a shame that Washington threw that line away in the performance I saw).

Larry is O’Neill’s beloved “Old Foolosopher:” the cynical barfly who says he just wants to be left alone but who privately gets great pleasure out of being surrounded by his fellow bums -- a collection of eccentric characters referred to by one of their own lot as a “who’s who of dipsomania.” In turn, Larry is the object of affection to all. The bartenders love him, the hookers dote on him, his fellow bums admire him and his sage words of drunken wisdom. If Harry Hope’s seedy saloon was transported to 1970’s Los Angeles, Larry would be Charles Bukowski.

So, if this is Larry Slade’s play, and I think I’ve just talked myself into being willing to defend that position, what can be made of David Morse’s portrayal? In the performance I saw, Morse’s Larry starts and ends the play, bizarrely, as an outsider. It is impossible to believe that his Larry is a part of this crew, much less the soulful center of it. In dress, appearance, and bearing, Morse seems to be channeling the late Robert Ryan’s take on the character as seen in John Frankenheimer’s magnificent 1973 film adaptation. Ryan was seriously ill with cancer during shooting, adding an extra layer of pathos to a deeply felt, superb performance that would turn out to be his final role (Frederick March is equally stellar in the film, as is everyone else in the ensemble, with the glaring exception of a grotesquely miscast Lee Marvin as Hickey). Ryan owned the role. But though Morse may possess a passing physical likeness to him in this production, the similarities stop there. Instead, Morse seems uncomfortable from the get-go, his hands constantly shoved deep into his pockets as though mechanically feeling around for a lost set of keys. He seems to take no joy in ribbing his fellow inmates at the bar; in fact, it seems as though he is acting in a different play altogether. His Larry seems to be nothing so much as an older version of Albee’s Peter at the zoo.. He seems disengaged, flat, strangely affected, and -- sad to say -- lacking in either warmth or charisma.

I don’t want to beat up on David Morse, who has proved himself again and again in other roles. Perhaps the odd choices for Larry’s personality and bearing were not made by him. Morse’s cause is certainly not helped by the fact that he is often stationed at the extreme left or right of the action, most likely to emphasize his self-stated position of being “in the grandstand,” watching the proceedings from a objective standpoint. But the effect is confusing, and seems ultimately wrong-headed, as does the production’s curious sound design. Early in Act One--as Larry introduces his sleeping friends to the young interloper Parrot, taking care to flesh out the backstory for each-- the strains of an old Gilded Age parlor song are heard being ponderously plunked out on a piano. But where is the music coming from? There is an upright piano onstage, but no one is playing it. Oh, it’s underscoring -- the cinematic kind, awash in the sort of ghostly reverb used to cue an audience to understand that we’re in flashback mode. But while the drama is indeed set in the distant past (1912, to be precise), “The Iceman Cometh” is decidedly not a memory play. Larry Slade is not Tom Wingfield, wistfully gazing back at people and events that once shaped his consciousness. Inarguably, the exposition O’Neill gives to Larry in the early going of the piece can be rough sledding for both actor and audience, but the decision to try to lift the proceedings with this kind of musical sentimentality feels like an act of desperation, as though the production somehow does not trust O’Neill’s iron-clad dramaturgy to hold its own.

Good things can be said about the production: it certainly moves briskly, and director George C. Wolfe has a deft touch with regard to bringing out O’Neill’s comedy. This may come as a surprise to those less familiar with the play, but there is a lot in “Iceman” that is very funny, and this production makes the most of it. In fact, if one were to judge the play purely on the basis of the audience’s reaction during the performance I saw, one might well think it a silly comedy -- more “Cheers” than “The Lower Depths.” Much of the rest of the cast acquit themselves well, especially Bill Irwin’s Mosher and Michael Potts’ Joe Mott, the latter receiving a well-deserved ovation for his speech that calls out the underlying racist atmosphere in Harry Hope’s saloon -- an issue that, happily, does not seem at all confused by the casting of Washington as Hickey.

And what of Washington, the reason that this production exists in the first place, and the reason that most will see it? He is excellent, probably the most likeable, charming Hickey ever seen (and that includes Robards, who brought more than a touch of menace and darkness to a the role that will always be his). Even when Hickey is at his most gratingly self-righteous, Washington is impossible to dislike. He is simply a delight to watch, and when he finally delivers his confession in the final act, he does so seated downstage center, breaking the fourth wall and talking directly to us, spinning his tale with bravura storytelling technique, casting us under his spell. The audience eats it up. This is what they came for.

Sadly, the promise and potential to be mined in the reuniting of the former “Elsewhere” stars for this production bears no fruit. When Washington leaves the room for the last time, he takes with him all of the air in this production.The play’s real punch that is the remainder of the action -- and indeed, O’Neill’s very thesis, his scathing indictment of latter-day humanity-- lands not as the knockout blow of a heavyweight champ, but rather as the harmless swat of a featherweight, a neat little ribbon to tie up an otherwise pleasantly diverting evening at the theater. The end of “The Iceman Cometh” should send us careening down into O’Neill’s bottomless, spiritual void, what should be an exhilarating, harrowing, plunge. Instead, we’re left safely peering in from the outside, safe, satisfied, unscathed.